Happy Thursday! Although invasive species usually make silent encroachments into new habitats, their impact is anything but quiet. Today we take a deep dive into some of the innovators helping solve for these challenges.

In today’s edition:

🔎 What is the problem with invasive species today?

🌳 Who are the hottest start-ups in the space?

💼 What are the challenges and opportunities for start-ups?

🔮 This is the first in a two part series written in collaboration with Rachel Lim from the Silverstrand capital team. Part two with our Invasive Species Market Map is here

👾 The Problem

Although invasive species usually make silent encroachments into new habitats, their impact is anything but quiet:

1. They can spread disease.

Example: Mosquitos, which have reached almost every corner of the globe, spreading yellow fever, malaria, and dengue associated with nearly half of all deaths over the last 200,000 years).

2. They can also decimate native prey populations that have never been able to evolve defence mechanisms.

Example: The European red fox in Australia. With no natural enemies, it is a known threat to 48 species of mammals, 14 species of birds, and 12 species of reptiles - many of them endemic.

3. And they can outcompete native species for resources like food & habitat.

Example: the Zebra Mussels in North America, whose females release up to 1M eggs per year, and that can attach to native mussel species, preventing the natives from moving, feeding, reproducing, or regulating water properly.

Adding insult to injury, the economic cost of these invaders has been astronomical—exceeding $1.288 trillion globally between 1970 and 2017, alarming costs that are projected to triple every decade.

Understanding the profound impacts these species have on our ecosystems is more urgent than ever. Given that 3,500 harmful species have been recorded by the IPBES (speaking nothing of the 37,000 invasive species that scientists estimate have actually occurred).

In this two-part series, Silverstrand Capital and Nature Tech Memos have teamed up to dive deep into the invasive species problem.

But first: What is an invasive species, anyway?

(Invasive species - a biological concept, or a social one?)

According to the IUCN, an "invasive species" is one that is:

Non-native (or alien) to the ecosystem under consideration (“animals, plants or other organisms introduced by humans, either intentionally or accidentally, into places outside of their natural range”),

And whose introduction is negatively impacting native biodiversity, ecosystem services or human economy and well-being.

In other words, “invasive species” are not equal to all non-native species - for a species to be considered invasive, it must not only be non-native.

It must also cause harm. Apple orchards, for example, might be found where apples did not originally evolve, but those apple trees would not technically be considered invasive, because they arguably lead to economic good for the orchard business, and did not cause ecological harm (depending on who’s asked).

TLDR; the invasive species concept includes both a biological and social component and is actually more fluid than most people realize, based on how society perceives harm.

How should we think about this, and why does it matter? Well, some ecologists, such as the author of this op-ed in Scientific American, have argued that non-native species can become a critical part of the new sites they inhabit, taking up the historical ecological function of now-extinct species.

When managing ecosystems, it’s crucial to consider the complex roles that non-native species might take. Rather than assuming all non-natives are harmful - nature, after all, is hardly that straightforward, and our management approach should respect its inherent complexity.

💬 The curve of a spread

Now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, let’s talk about some of the dynamics of how invasive species come to inhabit an ecosystem.

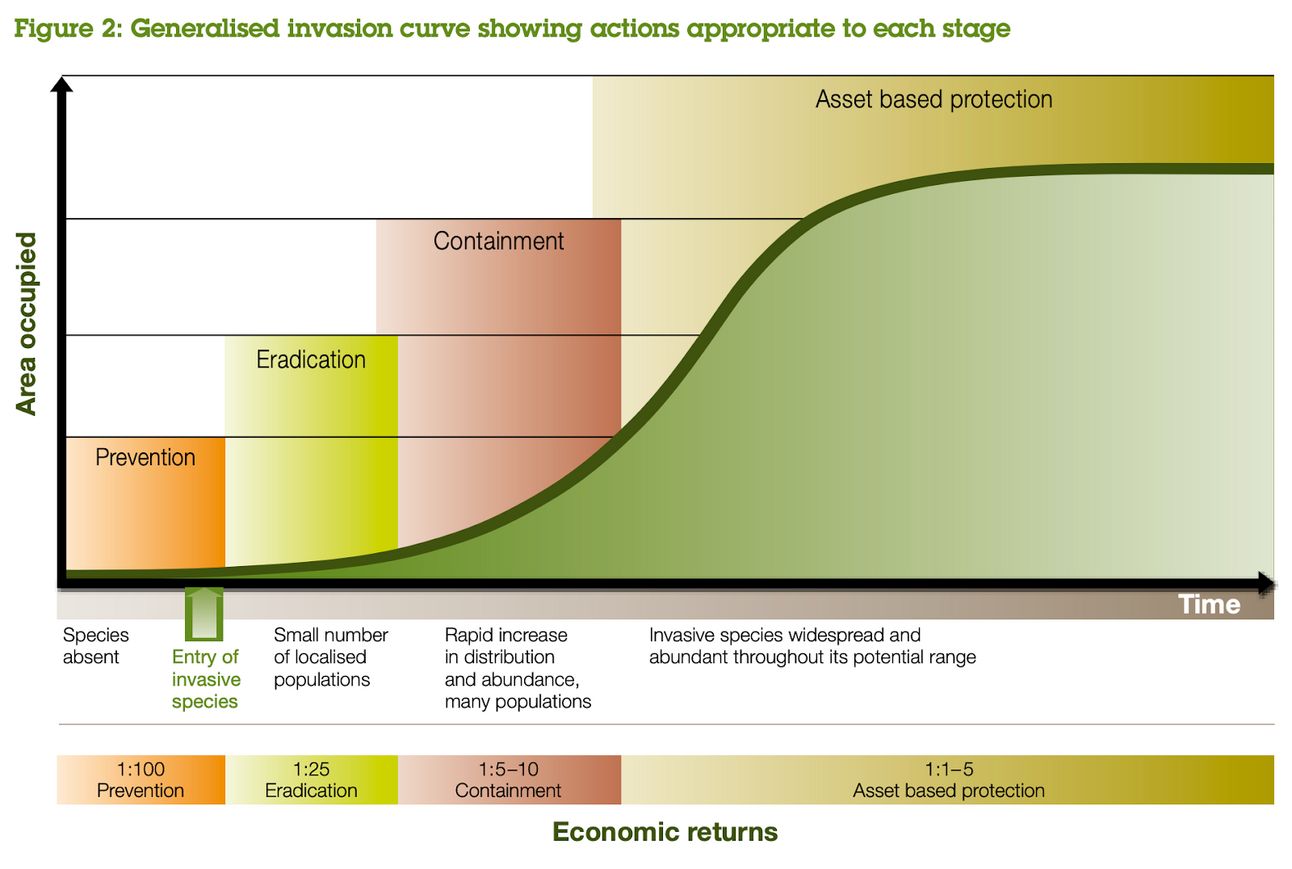

The invasive species curve, often referred to as the “invasion curve,” is a visual representation that tracks the spread of an invasive species over time and highlights the most effective management actions at each stage.

The curve shows how an invasive species starts with a small number of individuals (or even none, in the prevention phase) and then grows in population as it spreads throughout an area.

The curve is divided into several stages:

Prevention: When no species are present, the goal is to stop the species from entering. This is the first and most cost-effective stage to address. Research done by the Victorian government in Australia suggests an 1:100 economic return return on actions taken at this point.

Eradication: If prevention fails and the species has entered, the next best option is eradication, particularly when the population is still small and localized. This stage can still yield a good return, but the costs start to rise as the population grows. For every stage past prevention, it is critical that we consider population dynamics carefully. As has been the case in efforts to remove European Green Crabs from North American waters, or the over-use of chemical herbicides in certain “command and control” regimes, employing a black and white approach can cause unintended harm. Ecological communities are dynamic, and our management strategies must treat them with the sensitivity they deserve.

Containment: Once the species spreads beyond local populations and becomes more widespread, containment efforts aim to slow further expansion. The return on investment decreases at this stage.

Asset-based protection: When the invasive species has spread too far to contain, the focus shifts to protecting specific valuable assets (like critical habitats or infrastructure). This stage offers the lowest return on investment, as the species is now widespread and abundant, making full eradication impossible.

Although prevention provides the best return on investment, it is tragically underfunded. As in medicine, we tend to prescribe painkillers, not vitamins; One study found that in general, we spend about 10x more in mitigating damage than in management, with damage costs doubling in recent decades.

If we had to wager a guess, it’s probably because it’s difficult to act early because the benefits of prevention aren’t always visible, and it’s hard to measure the success of stopping something before it becomes a problem.

🗺️ Five start-ups to watch

If there’s one thing we’ve learned as we looked at the landscape of startups in this space, it’s this: there is a clear, and perhaps unsurprising concentration of solutions built for agriculture, and especially invasive insect pests.

Here, we’ve done our best to provide an illustrative look at companies working across industries, and across the curve of the spread. (Stay tuned for part two, where we’ll be sharing a wider map of invasive species startups!)

Rapid Aim (Detection & Prediction)

A precision pest management tool that can provide prediction and detection analytics for agricultural invasives, including highly invasive fruit flies in Australia

Latest Round: Seed; March 2021; $1.3M

Investors: Alberts Impact Ventures, Tenacious Ventures

News: RapidAim to deliver real-time moth monitoring on crop farmsThe Invasive Species Corporation (Biological Removals)

Discovering, developing, and deploying sustainable biological solutions to control a number of invasive species, starting in the US with the prolific Zebra and Quagga mussels and Asian Carp

Latest Round: Pre-seed; November 2023; $2.5M

Investors: Silverstrand Capital (Read our investment notes on this company here)

News: Invasive Species Corporation Co-founder & Exec. Chair, Pam Marrone is Inducted in the National Academy of EngineeringOxitec (Biological Removals in Agriculture)

A developer of biological gene-based solutions to control pests that transmit disease, destroy crops and harm livestock, including mosquitos.

Latest Round: Grant; May 2022; $18M

Investors/Funders: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Wellcome Trust

News: Djibouti Advances the Fight Against Malaria with Launch of First Full Pilot Season of Friendly™ Mosquitoes in Africa, Targeting the Invasive Anopheles stephensiWildlife Drones (Tracking Movements for More Efficient Removals)

Uses a proprietary aerial radio telemetry system to track species movements, for use cases including planning and managing invasive species eradications more efficiently.

Latest Round: May 2023, Undisclosed

Investors: Uniseed, Stoic Venture Capital and Draper Startup House

News: On foot and by drone, radio tracking helps rehabilitate pangolins in VietnamInversa (Novel Materials)

Turns destructive invasive species such as Lionfish into alternative leathers to protect ecosystems like the coral reefs in the Caribbean, the Greater Everglades ecosystem, and Mississippi River Basin

Latest Round: January 2024; Undisclosed

Investors: Superorganism, Meliorate Partners

News: Biodegradable fabric might be the next best thing in clothing

🌬️ Conclusions

Despite the fact that invasive species can cause massive damage in other industries like infrastructure (Fire ants, for example, damage infrastructure by digging near and undermining roads and structures, with projected annual costs of over $500M in Australia alone), our search yielded few obvious startups that we could dig deeper into.

Are you working on under addressed industries that still face huge damages and impacts from invasive species, or have some insights into what market barriers exist in these spaces?

We’d love to hear from you!

Thanks for reading, and to Rachel Lim from the Silverstrand capital team for collaborating with us on this piece.

In part two, we’ll be exploring solutions that tackle biofouling - a fascinating area that proactively prevents the spread of invasive species from the source, and a rare set of solutions that address the first, deeply underfunded part of the invasive species curve. Check it out here!